Earlier this week, the Supreme Court issues a 5–4 ruling in the Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute case that allowed Ohio to continue its practice of purging voter rolls for voters who were deemed “ineligible” by virtue of non-voting or not responding. So, for example, if you fail to vote in a federal election and don’t respond to a federal mailer confirming your address, and subsequently don’t vote for two more consecutive elections, the state has the right to remove you from the voter registration list.

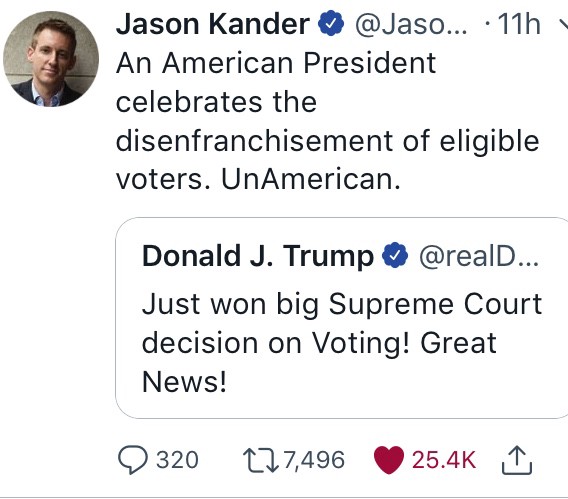

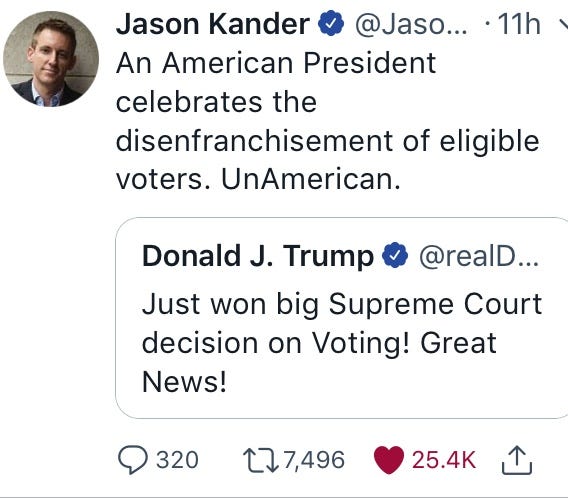

The chilling effect of this decision is to effectively desecrate our democracy, or whatever part of is left under this administration’s assault on it from all fronts. The tweet above shows the President’s response to that disenfranchisement — that of jubilation — one that will surely impact the poor and black voters of Ohio the most.

What is notable is not Trump’s reaction itself, but the predictable ways he and members of his administration have all engaged in the slow, but steady march towards silencing, minimizing, and erasing voices of dissent, and how it mirrors tactics abusers use to discredit and to disempower their accusers. Less well-known, is the fact that abusers’ coercive tactics escalate at times when their victims make attempts to assert their autonomy or seek independence. As Evan Stark share in Episode 2 podcast, the major outcome of “coercive control” is “suppressing a person’s autonomy, rights and liberties.” These tactics are used interchangeably in both the personal and public spaces, with the intent for those exercising it to maintain power and control.

A good example of how this tactic appears in private relationships can be found in the survey results of a public university’s students about their experience with sexual violence. In Episode 5 of en(gender)ed, my conversation with our guest referenced the CUNY Sexual Violence Campus Climate Survey, a requirement under the NYS Education Law 129B, the state’s “Enough is Enough” law.

Questions on Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) were posed to CUNY students, but only limited to one of the following four criteria: (1) physical threats to harm, (2) physical harm in the form of a push, shove, slap, punch, hit or kick, (3) requests for surveillance and keeping track of student, or (4) financial abuse by controlling or withholding finances. In other words, for students who might be unfamiliar with the term “coercive control” and the ways in which it may be enacted in a romantic relationship, a whole set of behaviors were not addressed or included in the survey.

Of the close to 32,000 responses received from this 2016 CUNY student survey, approximately 70% of the respondents were female, compared to 57% for CUNY overall. Based on the definition provided in the survey, ten percent of respondents identified as having experienced at least one incident of IPV in the past twelve months preceding the survey. Of the students who reported that a current or former romantic partner had made physical threats of harm to them, 64% reported that it prevented them from studying, 42% reported that it caused them to miss class, 45% reported that it caused them to delay or miss a test or hand in an assignment on time, and 11% reported that it caused them to leave school.

Although the students who experienced physical threats to harm had the highest rates of negative impact on their college persistence, the numbers from the other three questions revealed a disturbing, but expected trend for those of us who work with domestic violence survivors — that abuser tactics center around reducing the autonomy and agency of their partners, and efforts to participate in self-empowering and/or self-improving activities such as school or work can often pose a lethal, invisible risk.

In his seminal book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paolo Freire described “education as the practice of freedom” — and, therefore — a force for expanding democracy. It is no wonder that Trump and his supporters want to enact laws that limit the voice and power of the most marginalized voices in our society — doing so only strengthens his power and reduces ours, concentrating power in the hands of the few, white, straight, wealthy, men. Understanding this common “coercive control” tactic, and recognizing it as a “liberty” crime, as Evan Stark so aptly coins it, can help us all better connect the ways abuse of power is manifest in our lives, to confront it, and to develop the policies and solutions we need to address it.